Recently, a new group calling itself ‘Protect App-Based Drivers and Services’ (PABDASA) launched a new website in an attempt to shift public perception against California Assembly Bill 5 (AB5). But what is PABDASA and will it benefit drivers? RSG contributor Gabe Ets-Hokin breaks down what you need to know about PABDASA below.

California Assembly Bill 5 (AB5), which goes into effect January 1, will reclassify most gig workers: workers for Uber, Lyft, Postmates, Grubhub, DoorDash and a myriad of others as employees, making these companies’ paths to profitability much harder.

In response, Uber, Lyft and DoorDash committed $90 million, and Instacart and Postmates pitched in another $10 million, to sponsor a statewide ballot initiative to overturn it. I was curious: will pay increase or decrease? What kinds of benefits will they give us? Will it be a better deal than what we have now?

Luckily, on October 29, Protect App-Based Drivers and Services posted the text of PABDASA on its website. I’ll go through the important sections with you and then let you know if I think we’ll have a better deal under PABDASA or as employees.

Pay Under the Protect App-Based Drivers and Services Act (PABDASA)

Let’s get right to the meatloaf: pay. After a flowery introductory section outlining the goals of the new law, and another section that reinforces the anti-Dynamex argument that the companies have made for years stating they don’t have any real control over drivers, there’s Article 3, Compensation. It establishes that drivers shall always be paid a minimum that’s greater than a “net earnings floor” and can always be paid more.

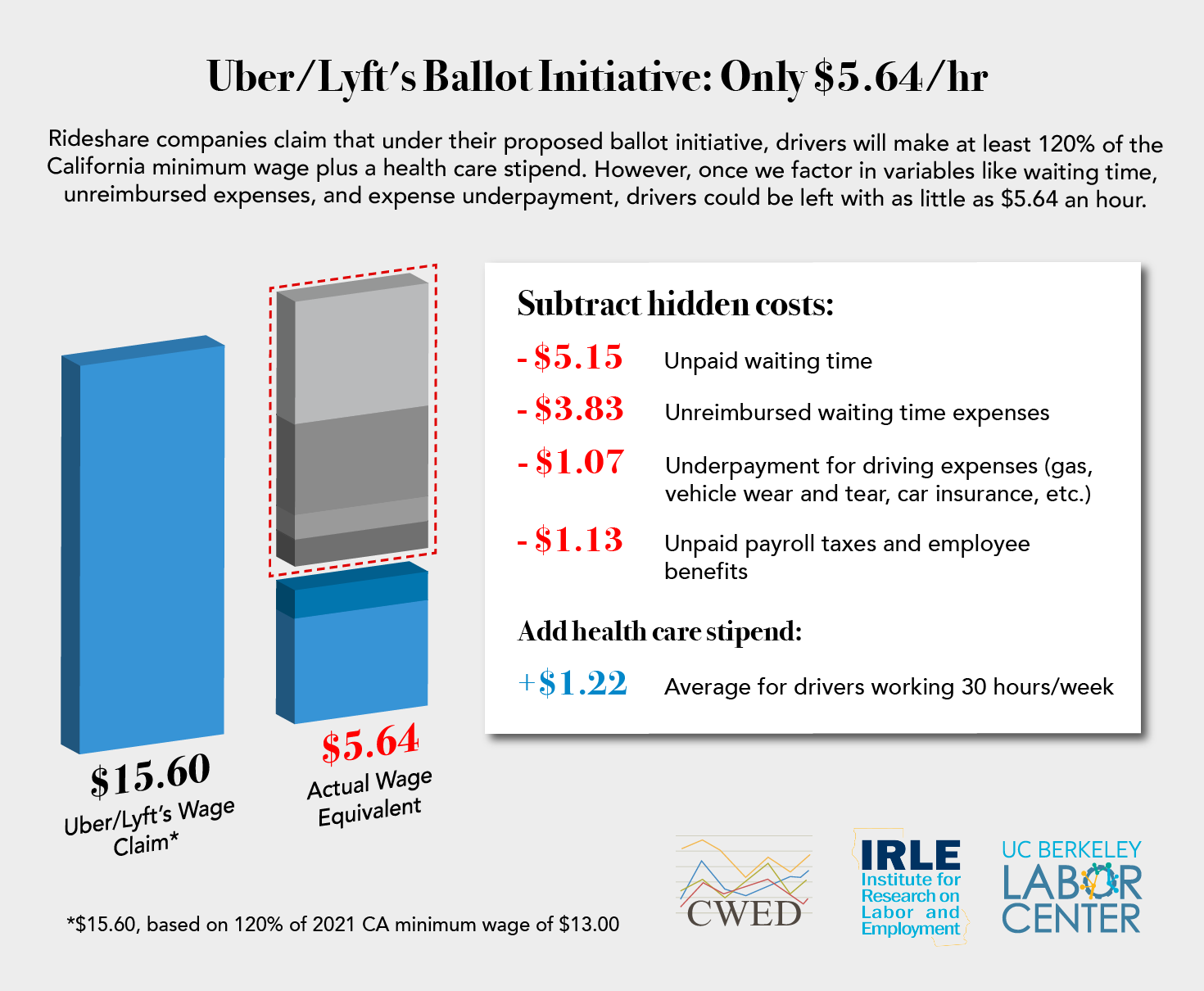

Ken Jacobs and Michael Reich of the U.C. Berkeley Labor Center found driver earnings would be around $5.64 an hour, but they also deduct unpaid mileage reimbursment during wait times, unpaid employee benefits and underpaid mileage reimbursement. We here at Rideshare Guy think that before deducting for actual expenses, you’ll likely be guaranteed a minimum wage of $15-16 an hour if you drive in a reasonably busy place during reasonably busy times. Deducting the IRS mileage rate of 58 cents per mile can drop your pay to about $5 an hour if you drive 20 miles per working hour! Drivers of high-maintenance gas-guzzlers, beware.

The main gripe we have with this U.C. Berkeley analysis is that they used the 58 cents per mile figure for a driver’s costs, and that is a very conservative number. A used Prius might only cost a driver 20 cents per mile.

Uber and Lyft stridently maintain that PABDASA sets a floor, not a ceiling, so just as passengers might tip you, Uber and Lyft might pay you more. The floor is determined by multiplying the applicable minimum wage (for the city or county you pick up in) by 120 percent and adding 30 cents per mile. Sounds good, right? It would be great…if they paid you from the second you made yourself available in driver mode to the moment you went offline. But they won’t. Instead, you’ll be paid for your “engaged” time, which starts when you accept a request and ends when you end the trip or delivery.

But how are we going to determine that number? If only Uber and Lyft had that data and made it freely available to scrappy RSG muckrakers. Oh wait! They did! In 2018.

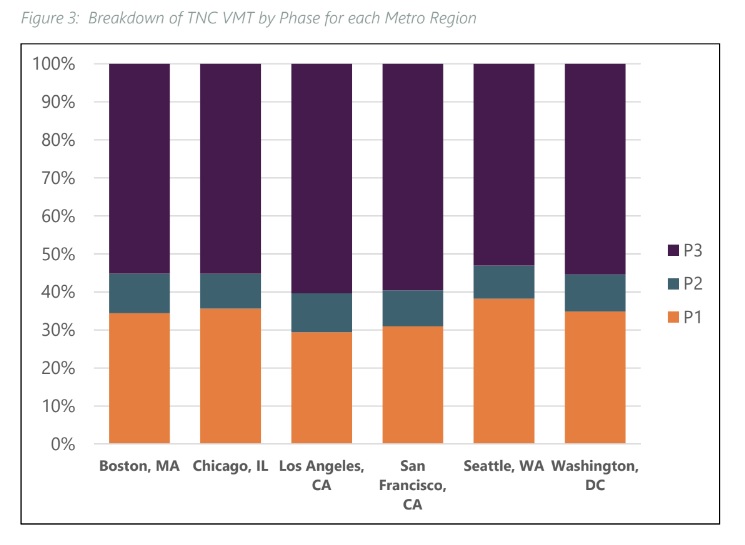

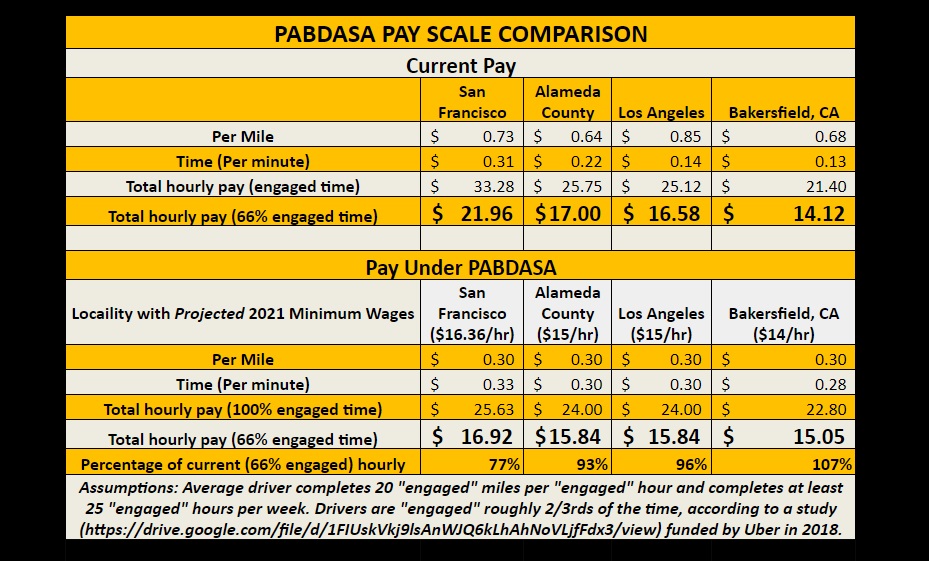

A report by high-end transportation consultants Fehr and Peers (paid for by Uber and Lyft) in 2018 revealed we’re “disengaged”–logged into the app but with no requests–about a third of the time. So in San Francisco, for instance, where a ‘grandfathered’ driver is paid 73 cents a mile and 31 cents a minute, if we assume 66% engaged time, you earn $21.96 per each hour you’re online (on average). Of course, that doesn’t include tips and bonuses.

Under PABDASA, if we assume 66% engaged time, you will earn less in some places, more in others, which is why I ginned up one of my world-famous spreadsheets to figure it all out. Is PABDASA better or worse? The answer is some of us will make more and some will make less.

In San Francisco, under PABDASA, drivers will earn at least $16.92 per hour assuming 66% engaged time. Note this is just the minimum pay, so if I’m averaging $21.96 per hour right now in SF without PABDASA, I’m not really sure how this would help me at all. And additionally, if my expenses are $3 per hour, I’m now actually making below minimum wage of $16.36 per hour in 2021.

To make this spreadsheet, I had to start with some assumptions. Primarily, I had to guesstimate how many miles an average driver completes while “engaged”–that is, while on the way to a pickup or while actually transporting the passenger. Under PABDASA, we won’t get paid while the app is on unless we’ve accepted a trip.

I looked at five years of my own trip data, which shows I average 15 paid miles for every hour my apps are online. Since that number is from the actual trip mileage I get from Uber and Lyft reports, it doesn’t include the time spent driving to the pickup, which PABDASA would pay us for.

I seldom drive more than five minutes to pick up a passenger, and my lifetime completed trip average is 3.3 an hour, so I decided to give PABDASA the benefit of the doubt and figure the average driver will complete about 20 miles per engaged hour. Of course, it’s possible that in less-populated areas, a driver may do 25 or 30 miles per hour on average (especially if you’re following a destination-filter strategy), but that seems extreme.

Benefits Under PABDASA

Under the Affordable Care Act, large employers must offer health-care coverage to 95 percent of their employees. That’s no good for Uber/Lyft! PABDASA requires companies to pay full-time drivers about 83% of the premiums for a Covered California Bronze plan, which according to Protect App-Based Drivers and Services’ press representative Stacey Wells’ best guess is $367.36 a month. But it’s not automatic: gig companies will provide a 50% stipend to its drivers if they work 15 or more engaged hours a week, 100% for more than 25.

Interestingly, you can double-dip if you work enough hours with two or more companies. That can be a double-edged sword, as it may restrict how much time you can spread between the two apps. So if you want to be assured of getting your full stipend, you’ll likely have to choose one company over another. PABDASA requires companies to figure your hours over each quarter, so that could help; if you don’t complete enough hours one week, you can make it up the next.

So to get this benefit–which works out to $367.36 a month, an estimate provided by Ms. Wells–you’ll need to work at least 33 hours a week (25 hours plus 33 percent). Note that the companies may ask for proof you’re enrolled in an ACA health-care plan. If you’re on MediCal, MediCare, VA coverage or a spouse or family member’s plan, you may not qualify for this stipend. Uber and Lyft always maintain that only a small percentage of its drivers work more than 10 hours a week, so we didn’t calculate the extra $3 an hour a 120-hour-per-month driver might make from that.

Other benefits include disability and death/dismemberment insurance, but it’s unclear if Uber/Lyft would pay the premiums. I think they would: not a bad little perk, but a fraction of what actual employees are due in California.

Flexibility Under PABDASA

Ironically, there’s no section or article titled “Flexibility,” the main thing the anti-AB5 argument has going for it. However, it does have an article declaring that “an app-based driver is an independent contractor and not an employee or agent with respect to his or her relationship with a network company if… the network company does not unilaterally prescribe specific dates, times of day, or a minimum number of hours during which the app-based driver must be logged into the network”.

It also gives us the right to refuse (nothing about cancelling) trips and work for other companies.

What Kind of Rights Will Workers Receive Under PABDASA?

As far as rights go, PABDASA is pretty light. App-based workers can’t collectively bargain, aren’t subject to the very-lengthy California Labor Code, and good luck lobbying the union-and-worker friendly California legislature: PABDASA is a jealous lover and requires a 7/8th (88%) majority for amendments. So if we decide we don’t like the new law after a year or two, guess what? Tough luck. Raise your own $100 million war chest and go back to the voters, because you probably couldn’t pass a bill in the California legislature proclaiming “ice cream is delicious” with a 7/8th majority.

It does make it a bit harder to deactivate gig workers, though. It outlaws at-will termination and requires an appeal process, protects against sexual harassment and mandates investigation of claims of wrong-doing. It also requires drivers to undergo (unpaid) safety training. It also codifies Uber and Lyft’s policy of automatically deactivating any worker reported for possibly being under the influence of alcohol or drugs, as long as the reporter “reasonably suspects” that’s the case.

What PABDASA Means for Drivers

Will PABDASA be good or bad for you? Here’s the bottom line. California minimum wage will be $14 an hour when the proposed law takes effect in January 2021. That means a California Uber or Lyft driver, working for a typical rate now, will likely make a bit more than that…before you deduct your expenses, which could suck another $3-10 an hour out of your pocket.

Also, this is California legislation, so if you’re in any other state it won’t directly affect you, unless Uber and Lyft use it as a blueprint to change the law in your state.

The life and disability insurance is nice, but this kind of minimal coverage is cheap purchased a la carte. As for the appeals process and at-will deactivation protections, well, we’ve all had experiences with Uber and Lyft that tell us these things will likely give the companies the benefit of the doubt, like binding arbitration. I imagine Uber’s appeals board will be staffed by some kind of AI, or worse, their current staff that answer the customer-service phone numbers. PABDASA has no language regulating or overseeing the appeal process, so I’d expect it to not favor drivers.

For the next 12 months, uninformed media as well as paid mouthpieces for Uber, Lyft and the delivery services will repeat the misleading and incorrect claim that PABDASA pays 120% of minimum wage. In fact, after vehicle expenses, it will likely pay less than minimum wage unless you have very low costs and a passenger in your car more than 66 percent of the time. And what about drivers who use Fair, Lyft Express Drive or other rental services?

To be fair, Ms. Wells pointed out a few things. First, PABDASA’s language doesn’t say Uber and Lyft have to pay us the minimum: they can pay us any amount over the payment floor. I agree, and if this passes, I don’t expect our pay to immediately plummet to the new, lower amount. But I also think Uber and Lyft will eventually be forced to lower it as much as they can to avoid bankruptcy, even if the folks at those companies are as kind and benevolent as they want us to believe.That’s because investors, board members and shareholders will demand squeezing us as much as possible so they can become profitable.

Ms. Wells also pointed out that Uber and Lyft just can’t be expected to pay us while we’re “not working.” After all, she told me on the phone, we’re “free to do anything we want” (I’m paraphrasing) in between pings. We could be writing a novel, or standing next to our Prius practicing our golf swing, or trying out one of the best gig jobs out there.

That’s reasonable: in fact, maybe we should deduct Uber’s software engineers a pro-rata amount of their annual salary while they’re using the bathroom, enjoying a lavish company-provided catered meal or chatting with a co-worker and see how that goes over with them.

As written, PABDASA has lots of nice-sounding language but clearly benefits companies more than drivers.

Find the text of the proposed law here.

Drivers, what do you think about PABDASA and what it offers drivers?

-Gabe @ RSG